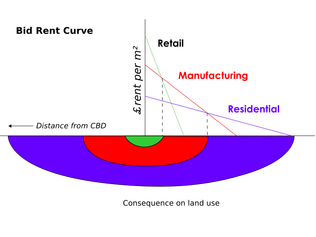

"Bid rent1" by SyntaxError55 "Bid rent1" by SyntaxError55 So, why do we think cities can be shaped by a transit improvement? For one, we've seen it happen. Streetcar suburbs - my favorite example - are one of many physical marks on the U.S. landscape that are directly associated with transit investments. We see the empirical evidence in neighborhoods, downtowns, and corridors. But what actually explains the relationship between transit investments and the shape of our cities? Well, I'm going to get a bit (okay, a lot!) wonky here and provide the urban economist's perspective. To start, almost all explanatory economic models of urban form rely on transport costs to define the spatial relationships of residents, firms, and regional geography. The economic theories would suggest that any transit service that changes the cost of accessing places in a city will impact the attractiveness of some places relative to others and, therefore, influence land values. In general, the theory suggests that transit-served places will be more valuable than they would if no transit were provided. At the core of it, theory suggests that people's willingness to pay for a location (land rents) are based on a competitive land market in which users who pay the most will gain the right to productively use a piece of land; therefore, the most productive land achieves the highest rent (Ricardo 1891). Productive use of the land includes transmitting people and goods to other locations (taking the milk to the market with ease or locating the market where the customers are). So, the more money someone can make on the land, the more they pay for it. Here's where transit comes into the picture. A land user’s ability to pay for land increases as transport costs decrease; thus, land that requires users to incur lower transport costs will be higher priced (von Thunen 1966). More generally, land with high accessibility—the relative ease of moving between locations of interest—will have higher value compared to less accessible land (Giuliano 2004). Because transport infrastructure consists of networks (links+nodes), land values are typically higher closer—but not too close—to network access/transfer nodes like intersections, highway onramps, or transit stations. Being too close to the negative externalities of transport, like noise and pollution, may have unfavorable impacts on land values. Thus, you might find land values are lower at the midpoints of links in the system (i.e., near the noisy train tracks and far from the stations; near the freeway but far from the exit). In some of the earliest work on the subject of transport’s influence on urban development, theories on location and site rent in rural settings (von Thunen 1966; Christaller 1966; Ricardo 1891) were adapted to central city-oriented urban models by Alonso (1964), Mills (1972), and Muth (1969) (collectively called the monocentric city models because they assume everyone works in the central business district (CBD)). This is fundamental and you cannot get out of an urban economics class without hearing that jumble of names a few times! Their collection of theories suggested that firms and residents make budget tradeoffs between CBD-based transport costs and land costs. Since people will pay more for the land when they have to travel less, their models suggest that different land users will generally end up outbidding one another for access to places various distances from the heart of town. The resulting "bid-rent curves" of different land users explain general observations of employment centrality, declining densities as one moves further from the CBD, and diminishing land costs as distance from the CBD increases. This is typically depicted as concentric circles where the bullseye is highly valued, high-density office buildings and then everyone else ends up in surrounding rings that are progressively less valuable and less densely populated/utilized. (Check out the graphic at the top of the post for one such depiction.) Based on these simple models, one can make some predictions about urban form as transport costs rise or fall. Of particular interest since we build transit to reduce transportation costs, the models predict that cities spread out as transport costs decline. Yes, all else equal, transit investments can be expected to help places sprawl! Mohring (1961) used the monocentric model to demonstrate how land markets would respond to the introduction of a radial transport investment. Assuming all else equal, certain locations would receive benefits and others would lose value as land markets adjusted to new accessibility gradients. Relaxing some constraints of the model demonstrated how densities, urban boundaries, trip frequency, and overall urban form changes would respond directly to the new accessibility provided by the infrastructure investment. As with all of the CBD-oriented models (and economic models in general!), Mohring’s model made assumptions that allowed for an analysis that ignored other location decision factors, the stickiness of parcelization, the durability of building stock, and other considerations. Most of these urban economic models assume that residents make location decisions based, for the most part, on accessibility. However, theory suggests that firms experience other benefits that inform their location decisions. The firm location literature of Weber (1969) and spatial economy theory of Isard (1956) add a finer grain dimension to discussions of urban form and have been the basis for newer and broader models of urban development. In general, the Weber and Isard-style models describe a tension between locating firms close to one another to exchange outputs more easily and locating firms farther away from one another to be closer to production inputs. In his assessment of where firms will theoretically locate, Weber considered input-output transport costs and labor costs to determine a least-cost firm location. As transport costs change, potentially through the addition of transport capacity or the congestion of an existing transport link, optimal locations may change. Krugman (1993) added to the theory by including economies of scale in the analysis. While a firm may have started producing a particular good because of a local market, economies of scale may encourage firms to produce even more of the same good in that market rather than distributing their production across other markets. This helps explain how, amongst other factors, declines in transport costs have allowed certain geographies, as well as their incomes, to grow disproportionately. It also explains an upward trend in firm size as transportation costs have declined. Economies of scale that occur external to firms are considered agglomeration economies of scale. The literature points to three types of agglomeration benefits: transport, labor, and information (Glaeser and Gottlieb 2009).

In sum, these economic theories help explain why various land users would value particular locations. Ultimately, Giuliano (2004) suggests that all of these theories are flawed but remain useful for both stylized understanding and anticipating the directional impacts of investments in our transport system. Generally, theory would lead us to believe that an improvement in transit service would:

References: Alonso, William. 1964. Location and Land Use: Towards a General Theory of Land Rent. Harvard University Press. Chatman, D. G., and R. B. Noland. 2013. “Transit Service, Physical Agglomeration and Productivity in US Metropolitan Areas.” Urban Studies, August. Christaller, Walter. 1966. Central Places in Southern Germany. Translated from Die Zentralen Orte in Suddeutschland by Carlisle W. Baskin. Englewood Cliffs N.J.: Prentice-Hall. Giuliano, Genevieve. 2004. “Land Use Impacts of Transportation Investments: Highway and Transit.” In The Geography of Urban Transportation, Third Edition, Third Edition. The Guilford Press. Glaeser, Edward, and Joshua Gottlieb. 2009. “The Wealth of Cities: Agglomeration Economies and Spatial Equilibrium in the United States.” Journal of Economic Literature Vol 47 (No 4): 983–1028. Glaeser, Edward, and Janet E. Kohlhase. 2003. “Cities, Regions and the Decline of Transport Costs.” Papers in Regional Science 83 (1): 197–228. Isard, Walter. 1956. Location and Space-Economy: A General Theory Relating to Industrial Location, Market Areas, Land Use, Trade, and Urban Structure. Cambridge Mass.: M.I.T. Press. Krugman, Paul. 1993. Geography and Trade. Leuven ;Cambridge (Mass.) ;;London: Leuven university press ;;MIT press. Mills, Edwin S. 1972. Studies in the Structure of the Urban Economy. Johns Hopkins University Press. Mohring, Herbert. 1961. “Land Values and the Measurement of Highway Benefits.” The Journal of Political Economy Vol. 69 (No. 3): pp. 236–49. Muth, Richard. 1969. Cities and Housing: The Spatial Pattern of Urban Residential Land Use. University of Chicago Press. Ricardo, David. 1891. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. G. Bell and Sons. von Thunen, Johann Heinrich. 1966. Isolated State; An English Edition of Der Isolierte Staat. Translated by Carla M. Wartenberg. Oxford, New York: Pergamon Press. Weber, Alfred. 1969. Theory of the Location of Industries. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

0 Comments

|

AuthorIan Carlton is a transportation and land use expert specializing in transit-oriented development (TOD). He helps clients - including transit agencies, planning departments, and landowners - optimize real estate development around transit. Archives

March 2019

CategoriesSpecial thanks to Burt Gregory at Mithun for permission to use the Portland Streetcar image above.

|

Photo from permanently scatterbrained

RSS Feed

RSS Feed