I feel like I should apologize to everyone because I'm consistently being a wet blanket when folks bring up a recent report about Fruitvale Transit Village. I tell them that they may not be able to afford their own set of Villages and that we'll likely need to keep looking at a suite of other tools to address their gentrification concerns. I do a lot equitable TOD and joint development-related work and our clients express many concerns about the gentrification and displacement impacts that TODs can have on communities, so it was great to see that LCCI at UCLA put out a policy brief in March about a victory in this regard. The study got a lot of media coverage, at least in part because of the optimistic finding that the Village stymied displacement. This study found that the Fruitvale Transit Village TOD increased the socio-economic well-being of residents in the immediate neighborhood while preserving the area's diverse racial/ethnic diversity. That's great! This is a wonderful example of a TOD where displacement concerns have not come to fruition. It's well worth examining! However, I am concerned about some commentary related to the study's findings. For example, Brock Keeling at Curbed was full of optimism: "Perhaps the only downside of the project—the languid time it took to get moving." In particular, CityLab put out an article that quoted the study's lead author, Sonja Diaz, who said, “This strikes me as a scalable project to ensure that there is economic mobility and opportunity for the most disadvantaged while still being something that makes economic sense for the wider community.” But from a financial perspective, is Fruitvale a scaleable approach to addressing gentrification and displacement risks? I fall in the camp of the skeptics. Carolina Reid questioned the study's data sources and whether they are appropriate for reaching their conclusions, but let's assume for now that the findings are completely valid. I doubt that communities can afford to address gentrification by building their own Village projects. My own studies of TOD for the City of Los Angeles's Transit Corridors Strategy and stalled equitable TOD projects included case studies of Fruitvale Transit Village that found that more than two thirds of the funding for the Village's $69M first phase was provided by sources that required no repayment. Typically, real estate development relies on equity investors that seek to recoup their original investments and also demand an attractive return on top of that original investment. In addition, the Village's grant funds were complemented by low-interest loans with very beneficial repayment terms. Unlike a typical market-rate real estate project where something like two thirds of the funds come from loans, the Village's loans were a smaller part of the overall project's capital sources because the project was unable to generate enough income to justify larger loans. All that's to say that the numbers don't look good for replicating this across the country. A simple extrapolation suggests that hundreds of billions in grant funds would be required to copy this model across half of the country's fixed-guideway transit stations. Does anyone have a spare $100B to hand out to TODs? So, I'm hopeful that we can do more research into Fruitvale Transit Village to understand what elements of this noteworthy TOD are contributing to the wonderful results found in this UCLA study. If we can determine that some aspects of the TOD do more to address displacement than others, we can do a benefit-cost comparison. Hopefully there are some key elements that are easier to deliver than an entire Village that required $50M in grants. Boy, I'd like to be able to deliver that good news story!

0 Comments

It's been a while since I've been on the blog, but a recent TCRP project proposal on joint development brought me back to my senses! In fact, I've been so busy working on a ton of value capture-related projects professionally that I have not had time to write about some great research that has come out in the last few years. For one, TCRP's Report 190 covers a lot of great ground. Because there's nothing like a good story to help people understand complex topics, there are six interesting case studies in the report:

There are also some brief explanations of the usual suspects, including:

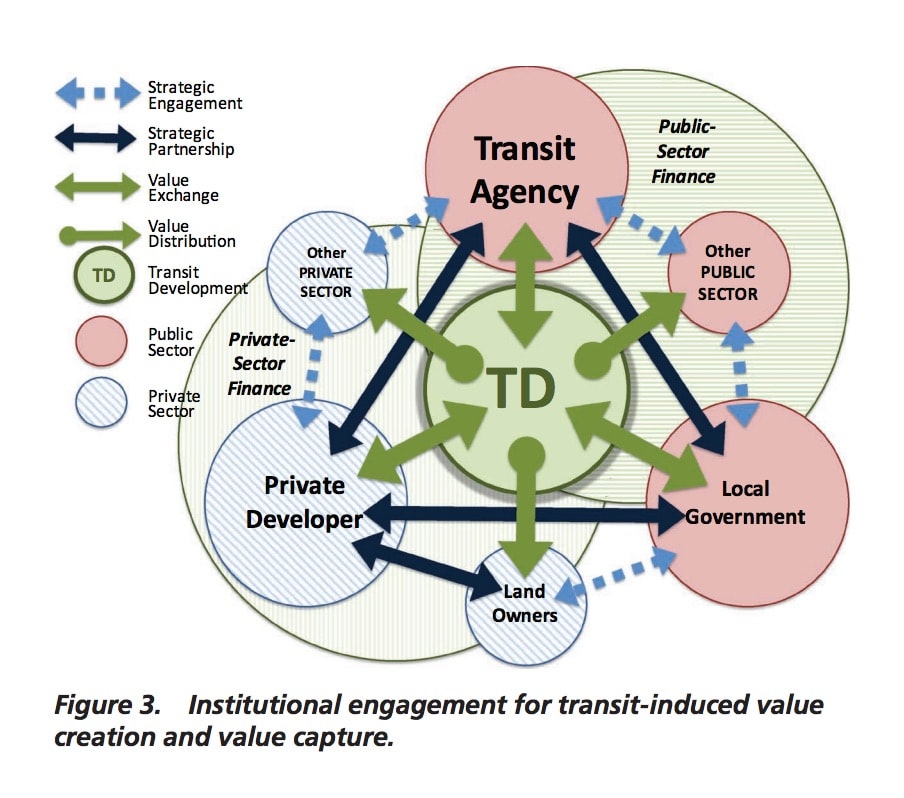

The most interesting parts for me were discussions on creditworthiness and institutional capacity. Seriously, we should talk about these more! For example, my clients are often very excited about a value capture mechanism and how it will help fund their particular project, but hardly ever appreciate the broader organizational factors related to bond issuance. On the other hand, my clients are often very aware of their institution's limited capacity to pull off value capture efforts in general (that's one reason to hire a consultant!). This report does a great job of illustrating the difficulties faced by agencies. I'm not sure if it was intentional, but this gnarly graphic is worth 1,000 words! Look at the confused relationships, overlaps, informal dotted lines, and dollars going everywhere! This report is a fun read for any value capture geek. Enjoy!

TCRP has put out a draft of TCRP Report 190. This is a much anticipated report in my world.

The lead author, Sasha Page, has experience advising clients on using federal programs (TIFIA and RRIF) to aid with value capture financing. In what I've read so far, his experience shows. Now, I'm looking forward to reading all the case studies.

Happy reading! In a post back in May, I noted that Chicago was seeking legislative authority from the State of Illinois to pursue TIF districts around transit projects. As discussed in Streetsblog Chicago, the bill passed and will allow CTA to collect incremental property tax dollars to fund system improvements. As noted by CityObservatory, the transit value creation argument may be weak enough that the redirection of these tax revenues to transit could be contested. At a conceptual level, the link between increased property values along these lines and the transit services themselves is murky. As with most value capture in the United States, the additional revenue won’t be based on some sophisticated econometric model meant to capture exactly how much extra value was created by transit: it will just assume that all new value is a result of the transit lines—or perhaps even the additional value of the rehabbed lines over their in-need-of-maintenance state. While evidence certainly suggests that rapid transit contributes to growing property values, many neighborhoods in central Chicago outside of rapid transit sheds have been growing in value as well, suggesting that there is a general trend towards the center city that goes beyond just transit access. And in some other cities, a general shortage of housing has been pushing up real estate values across entire metropolitan areas, making the connection even murkier. Perhaps this is a philosophical splitting of hairs. But if transit advocates justify new revenue by making the standard value capture argument and it doesn’t hold up, expect opponents to exploit that gap. For this model to be replicable, it will have to work well in Chicago, including providing substantial transit funding and overcoming challenges to its implementation.

|

AuthorIan Carlton is a transportation and land use expert specializing in transit-oriented development (TOD). He helps clients - including transit agencies, planning departments, and landowners - optimize real estate development around transit. Archives

March 2019

CategoriesSpecial thanks to Burt Gregory at Mithun for permission to use the Portland Streetcar image above.

|

Photo from permanently scatterbrained

RSS Feed

RSS Feed